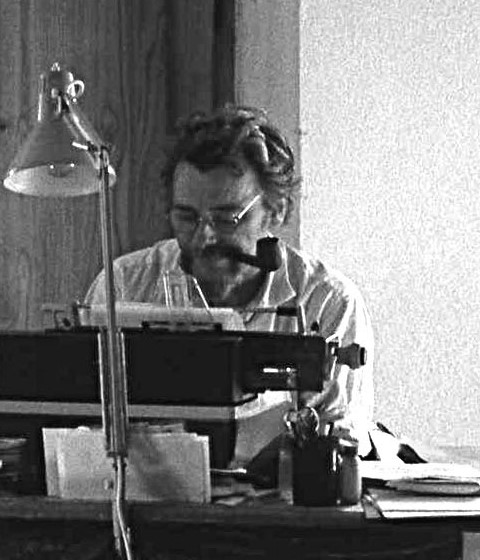

Hans Jürgen Fröhlich

Biography

by Alice Gardoncini, translation by Gail McDowell

Childhood and education

Hans Jürgen Fröhlich was born on August 4, 1932 in Hannover into a family of merchants. He was thirteen years younger than Levi, and thus belonged to the generation that experienced World War II during their childhood: in September 1939 he had just turned seven years of age. He witnessed the 1939-’40 bombing raids on his city, as he recalled in various autobiographical works (Tandelkeller and Anhand meines Bruders), and shortly afterward his family moved to the town of Duderstadt, also in Lower Saxony. Fröhlich attended middle school there, and later enrolled at the Music Academy in Detmold, not far away. At the Academy, he studied under Wolfgang Fortner, one of the most famous German composers of his generation, whose style was marked by Bach’s counterpoint but also employed dodecaphony.

Right from an early age, Fröhlich was fascinated by music and literature: after being exposed to the works of Frank Kafka, he decided to dedicate himself entirely to writing (Hanuschek 2020, p. 1). Especially his early works were clearly influenced by musical and compositional experimentalism. After completing his studies, he began to work as a bookseller in an antique store and as a journalist writing on cultural topics for the radio and a number of newspapers.

Cultural journalist in Hamburg, literary debut

In the 1960s he lived in Hamburg and was a member of the Neosocialist League (“Neusozialistischer Bund”), a political circle headed by Kurt Hiller. His friend Wolfgang Beutin (1934-2023), the first of Primo Levi’s “German readers” of If This Is a Man, was also a member; it was he who gave Fröhlich Levi’s address. During that period, they both worked at the German radio station NDR (Norddeutscher Rundfunk), involving themselves with radio dramas and journalism on cultural topics. Fröhlich had artistic and literary aspirations as well as musical training; Beutin was a historian with deep political passions: Levi and his book lay at the intersection of these interests and fascinated both young men. When Ist das ein Mensch? was published in 1961, the two friends were 29 and 27 years old, respectively: the same age as Levi when he wrote Se questo è un uomo (If This Is a Man). But by then, the author was 42 years old, so this encounter was also an intergenerational one.

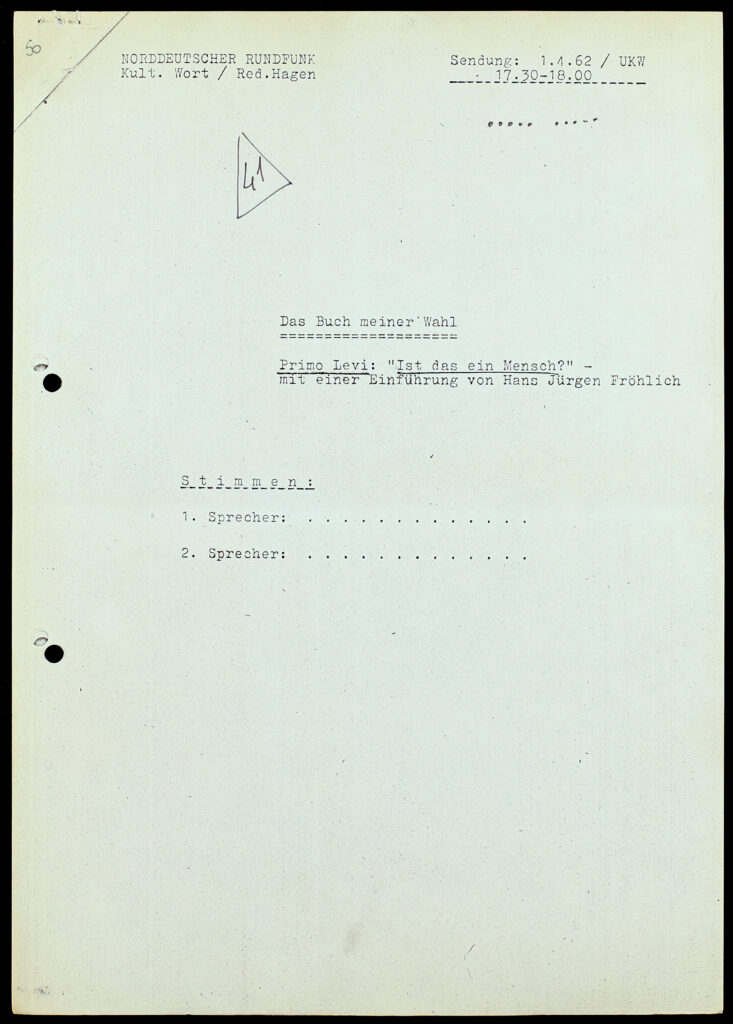

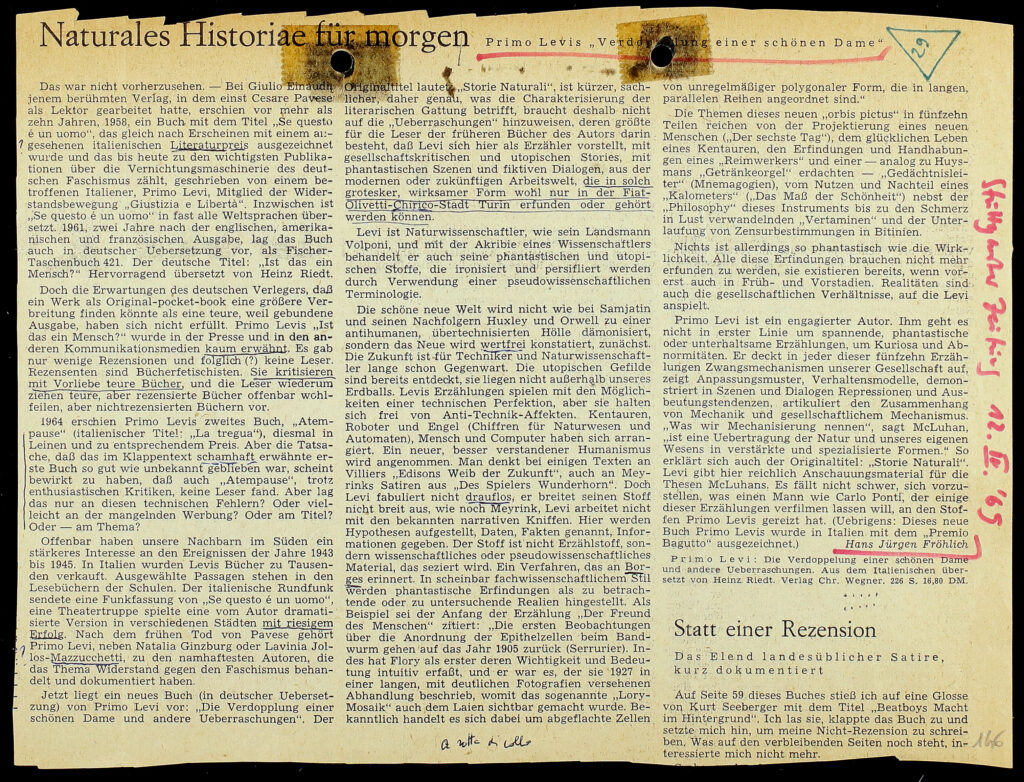

On April 1, 1962, NDR broadcast Fröhlich’s long radio review of Levi’s book on the program “Ein Buch meinerWahl” (“A book of my choice”). In this review, besides Fröhlich’s esteem for and interest in Levi, his passion for Italian literature was already evident. He showed himself to be a fairly good connoisseur, able to grasp and appreciate the references to Dante’s Divine Comedy.As early as the 1960s Fröhlich traveled frequently, and he passed through Italy many times: on one of those occasions, he met Levi in person in the second half of April 1962 in Turin (cf. Letters 65-67). In the meantime, he was writing a few theatrical works (the two plays mentioned in their correspondence are entitled Vier Wände and Samson, but they were never published; cf. Letter 70 dated July 30, 1962) and his debut novel Aber egal!, which was published in 1963 by Wegner Verlag in Hamburg. During those same years, Fröhlich worked as an editor at Claassen, a publishing company in Hamburg, translating various novels by Cesare Pavese, among others.

Searching for a second homeland, travels to the south

In the spring of 1964 he once again traveled in Italy, for about one month: on April 5 and 6, he was in Turin, where he met Levi for the second time. He then continued on to Florence, where he hoped to settle down, as can be inferred from his request that Levi intercede with Kurt Wolff on his behalf for an apartment (cf. Letters 82 and 83). The project seems to have fallen through, and Fröhlich continued his travels in search of the ideal place to write. In August 1966 he moved to Vienna, where he remained for about a year and completed his autobiographical novel Tandelkeller.

During his stay in Vienna, Fröhlich was frequently in contact with Austria’s intellectual and literary world: as early as July 1965 he invited Levi to take part in a gathering of young authors that was held twice a year in an Austrian castle near the border with Czechoslovakia (cf. Letter 84), and a few years later he took part in a series of days dedicated to studying and reading radio dramas, organized by Jan Rys (an Austrian author and the founder of an international center for radio drama research) in Unterrabnitz (Mahler-Tage 1971, p. 21).

Italy and his writing career

In 1969 Italy was once again at the center of Fröhlich’s life. His correspondence with Levi shows that the two of them met a third time in Turin that year. From that point on, Fröhlich lived primarily in Italy, moving among various cities. He and his wife bought a house near Lake Garda, at Bogliaco, and in the fall of 1969, after receiving a grant from the “Villa Massimo” German Academy in Rome, he moved to the capital, where he lived for one year. His first daughter, Anna Katharina, was born in 1971. This was a particularly prolific period in Fröhlich’s writing career: in a letter dated February 22, 1976 (Letter 089), he told Levi that he had published five books over the past few years, thanks to the peace and quiet on Lake Garda.

During the 1960s and early ‘70s, Fröhlich’s name began to circulate among Italian publishing companies as well. Research conducted at the archive of the Mondadori Foundation has made it possible to reconstruct the facts: in 1963, Mondadori received Aber egal! for consideration (reviews by Lavinia Mazzucchetti, Elio Vittorini, and Emilio Picco are held in the archive) and bought the rights for the publisher’s series “Medusa”; Italo Alighiero Chiusano was tasked with translating the book. Nonetheless, after several postponements, the project was ultimately shelved in July 1967 on the initiative of Giorgio Zampa, who had recently joined the publishing company (see the material held in SEE-AB, b. 30, fasc. 68, Frohlich Hans Jurgen).

Moreover, the International Literary Agency fund, also held at the Mondadori Foundation, shows that Fröhlich came into contact with Erich Linder in 1969 and that, through the agency, a few of his other novels were proposed to Italian editors for consideration (specifically, Tandelkeller in 1969 and Engels Kopf in 1973), but were rejected because they were considered too experimental and difficult to read in translation (SEE-Gdl, fasc. Frohlich Hans Jurgen).

After separating from his first wife, Fröhlich continued to enjoy a privileged relationship with Italy, spending his time between Munich and Tuscany, where he usually passed the summer months in a country house near Semproniano in the Grosseto province. Over the following years, he and his second wife had two more children, Johannes and Benjamin. On November 22, 1986, at 54 years of age, he died of a heart attack during a sojourn at the “Künstlerhof Schreyan” Cultural Center in Lower Saxony, where he had received a grant.

References and bibliography

Readers’ reviews on the novels by Hans Jürgen Fröhlich, in Fondazione Arnoldo e Alberto Mondadori, Milan, Archivio storico Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, Segreteria editoriale estero-AB, b. 30, fasc. 68 (Frohlich Hans Jurgen) and Segreteria editoriale estero-Giudizi di lettura, fasc. Frohlich Hans Jurgen. Correspondence with Erich Linder, in Fondazione Arnoldo e Alberto Mondadori, Milan, Fondo agenzia letteraria internazionale (ALI) - Erich Linder, Serie annuale 1969, b. 50, fasc. 29 (Frohlich Hans Jurgen).