by Alice Gardoncini, translation by Gail McDowell

An “expert”

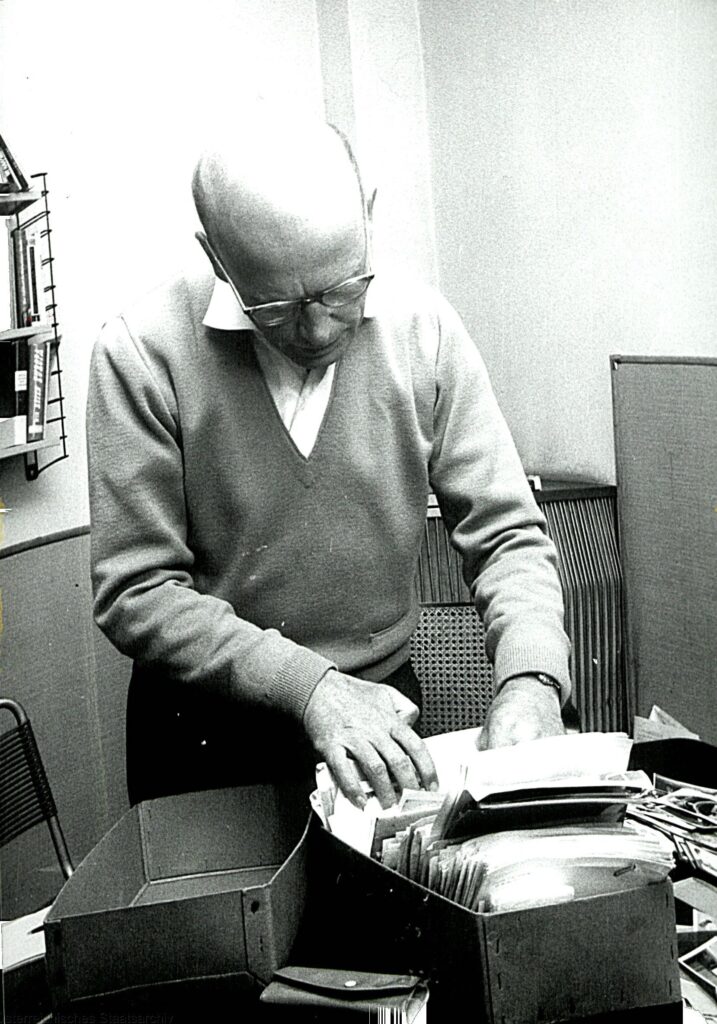

What remains of Hermann Langbein’s work is collectively held at Vienna’s State Archive, in the 293 folders that make up the Langbein fund. They were deposited at the Archive one year after his death.

Consulting the folders and the files they contain in groups of three, what is slowly taking shape in the minds of the researchers who are reconstructing the political and historical commitment of this “formidable man” is the composite image of an enormous quantity of papers, clippings, photographs, address books, notebooks, and an apparently infinite number of lists. It is a metaphor in paper form that shows what it actually meant to fight for justice and the memory of Auschwitz from the postwar period to the 1990s.

Memory is not an object that can be defined once and for all. Instead, it is a shared archive that must be constructed piece by piece, by weaving together widespread, ramified networks of correspondence, by tracking down and collecting thousands of single ephemeral personal memories, and subsequently organizing, studying, and winnowing them. After six and a half years of imprisonment in various concentration camps, Hermann Langbein dedicated himself heart and soul to this work of a lifetime, from 1945 until 1995.

In his short story “That Quiet Town of Auschwitz”, Primo Levi called Hermann Langbein “an ‘expert,’ a former prisoner who today is a famous historian of the camps” (CW III p. 2281). In fact, today Langbein is well-known in Europe and (thanks to Levi) in Italy, primarily for having written one of the most detailed and authoritative historiographic works about Auschwitz (People in Auschwitz). But the category of historian is too tight a fit for Langbein: he was in fact something more, something that is harder to define, an “expert.” People in Auschwitz and the other books he wrote are actually only the visible tip of a submerged iceberg. To this day, the largest and most fruitful ambit in which he concentrated his energy is partially unrecognized because, by its very nature, this work had to be conducted in the shadows, before the spotlights were lit and attracted the attention of public opinion. In fact, this work was conducted in order for the spotlight to be focused on those people who needed to be at the center of the attention: the preparation of the Nazi criminal trials.

Starting with the lawsuit in 1955 against Carl Clauberg, a Nazi doctor who was repatriated to West Germany after spending seven years as a prisoner of war in the Soviet Union, and continuing with Mengele, Eichmann, and many other infamous Nazis, Langbein was a key figure in reconstructing, tracking down, and finding proof of Nazi crimes. The Nuremberg trials, the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem, and the Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt are three now-famous events that helped create juridical and philosophical categories that have become integral to law and moral philosophy; and yet the history of how justice in postwar Europe tried first to describe and later to persecute crimes that did not yet have a name is complicated and tortuous, as well as little-known and surprising in some of its aspects.

Nuremberg and denazification

Historiography has a hard time even just establishing exactly how many trials against Nazi crimes have been held from the post-war period to today, but the most recent research shows that, in West Germany (and later united Germany) alone, 36,393 criminal procedures were opened between 1945 and 2005, for a total of 4,964 trials numbering 14,693 defendants (who were found guilty in 48% of the cases, Eichmüller 2008, pp. 631-2). To trace a general overview of the phenomenon and contextualize Langbein and Levi’s personal involvement on the one hand, and on the other the proceedings they mentioned in their correspondence, it is a good idea to start by establishing an approximate periodization.

The first phase concerns trials conducted by international courts in the four occupation zones and by the various national trials that were held during those same years. Already before the end of the war, the Allies had agreed to create courts that would hold trials for crimes committed by National Socialism. The Moscow Declarations of November 1943 created two distinct categories of crimes: those committed in a specific territory, which were to be judged by local courts in the countries in which the crimes had been committed; and those perpetrated on the basis of “criminal principles,” which were to be judged by joint decision of the governemnts of the Allies.

The famous Nuremberg trials belong to the latter category. Between October 29, 1945 and October 1, 1946, it was an International Military Tribunal that judged twenty-four Nazi party officials during the main trial, which was followed by twelve further secondary trials. The governing law was the Control Council Law No. 10 (December 20, 1945), which instituted the new juridical category of “crimes against humanity.” The trial ended with nineteen convictions; twelve of the defendants were sentenced to death, including Hermann Göring, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Alfred Rosenberg, and Ernst Kaltenbrunner.

On the other hand, on the basis of the principle of territoriality, a criminal such as Rudolf Höß, the infamous commandant at Auschwitz, was only called on to testify as a witness in Nuremberg (in defense of Kaltenbrunner), but he was later transferred to Poland as a defendant in the trial for the crimes he committed at Auschwitz. He was sentenced to death by hanging and executed in front of the entrance to the concentration camp on April 16, 1947. Leonardo De Benedetti and Enrica Jona, from Piedmont, took part in this trial as witnesses (their depositions are dated March 22, 1947). They were accompanied by the president of the “Comitato Ricerche Deportati Ebrei” (Research Committee on Jewish Deportees), Massimo Adolfo Vitale, who also presented a deposition written by Primo Levi (Levi 2015, pp. 212-13).

For the Allies, the Nuremberg trials were meant to be an opportunity to condemn the National Socialist regime as a system, and to give German society a democratic reorientation. But even though German public opinion recognized the need to punish the guilty parties, it perceived the trial as an act of punitive justice of the winners against the vanquished, which had serious consequences over the following decade (Pendas 2006, pp. 10-11).

The silence of the 1950s

The process of denazification that the Allies envisaged and initiated during the immediate postwar period was meant to go hand in hand with the reconstruction of individual states, and specifically with the creation of two German states and their respective juridical systems. Nonetheless, after gaining autonomy and national sovereignty, in the 1950s West Germany not only abandoned Control Council Law no. 10 in favor of an ordinary law, with all the relevant limits (Ponso, p. 154), but more importantly, registered a drastic decline in trials against Nazi criminals. This was partly due to the inadequacy of its juridical system and partly to a substantial continuity between the ruling Nazi class and that of the newly-founded republic. Silence concerning the very recent Nazi past somehow became a prerequisite for the democratic stabilization of the Federal Republic (Lübbe 1983, pp. 587 and ff.). The first period of the Adenauer era was characterized by a series of sensational amnesties (the first in 1949 and the second in 1954) and by various scandals that called attention to former Nazis who were in key positions (such as Wolfgang Fränkel, Hans Globke, and Theodor Oberländer).

This was the context when the International Auschwitz Committee (IAK) was created in 1954, with Langbein as secretary general. One of the committee’s main goals was to locate and reunite former deportees, so as to gather evidence and testimony regarding the crimes that had been committed, in order to begin pressing charges. The first accusations soon followed, against the SS doctors Carl Clauberg (in 1955) and Joseph Mengele (in 1956).

This created a paradoxical situation, which Primo Levi summarized in an article that appeared in La Stampa on December 23, 1960. The occasion was the capture of Richard Baer, who had succeeded Höß as the commander at Auschwitz. Baer would have become the key defendant at the Frankfurt trial, if he had not died shortly before the trial began: “[…] the police and the courts have proved much less ready to complete the job of purging begun by the Allies. And so we have reached the disconcerting situation of today, in which an Auschwitz commander can live and work undisturbed in Germany for fifteen years, and the executioner of millions of innocents is tracked down not by the German police but ‘illegally,’ by victims who escaped his hand” (CW III, p. 2334).

The 1960s

But things were already changing: in 1958, German public opinion was confronted with a number of trials, including the Ulm Einsatzkommando trial (on April 28, 1958), which took shape from isolated investigations that were initiated almost by chance when Bernhard Fischer-Schweder (who had been a functionary of the occupying police in Lithuania during the war) filed suit to be reinstated. The magistrates began an investigation, and this brought to light the murder of over five thousand Jews by ten members of the SS. 173 witnesses were heard for the first time during the trial, and what caused the biggest scandal was the fact that all of the defendants were enjoying peacefully integrated lives in the West German economic miracle (Speccher 2022, p. 87).

At this point it became clear that investigations had to be conducted in a systematic way, and to that end the so-called Zentrale Stelle (Central Office of the State Justice Administrations for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes) was formed in Ludwigsburg, with Erwin Schüle as the first director, followed by Adalbert Rückerl. This, along with the nomination of Fritz Bauer as State prosecutor general, were preconditions both for the capture of Eichmann in Buenos Aires in 1960 (Bauer himself passed the information to the Mossad because he did not believe the German legal system was capable of intervening at that moment) and, soon afterward, for the large Frankfurt Trial that was held between 1963 and 1965.

In the meantime, the International Auschwitz Committee (IAK) published two important works that helped focus the public opinion’s attention on the topic of Nazi crimes. The first, in 1958, were the memoirs of Höß, which he wrote during his last year of life in prison as he awaited his execution. The book was such a success that it became one of the major sources of financing for the IAK during those years (Stengel 2012, p. 284). In Italy, the book was translated and published by Einaudi in 1960 and again in 1985, with a foreword by Levi (CW III, pp. 2704-11). The second publication was the anthology Auschwitz. Zeugnisse und Berichte, which appeared in 1962 after a complicated publication history (which is reconstructed here). The book also contained two chapters from If This Is a Man, and this marked the beginning of the correspondence between Langbein and Levi.

Also in 1958, new charges brought by Langbein (once again, in the name of the IAK) initiated an investigation that brought the SS Wilhelm Boger to the Frankfurt Trial. At this point, an epistolary conversation began between Langbein and the Central Office, accompanied by a feverish exchange of lists of defendants and witnesses, which Langbein personally drew up and sent to other survivors throughout Europe for corrections and additions. A number of official Auschwitz documents containing lists of deportees who were killed had miraculously survived a fire; Emil Wulkan sent these documents to Bauer and, as is well known, they proved to be decisive to the investigation. Nonetheless, it is difficult to overestimate the importance of the network of contacts Langbein activated, or his role as a mediator – at the height of the Cold War – with witnesses and authorities in the Eastern block. For example, it was he who prompted an invitation on the part of Kazimierz Smoleń, the director of the museum in Auschwitz, for magistrates in the West to conduct an inspection of the camp (Halbmayr 2012, p. 192).

In those same years, the investigations on Eichmann were conducted with the collaboration of Langbein, Simon Wiesenthal, Henry Ormond, and Thomas Harlan (see the relative Insight). These investigations resulted in Eichmann’s arrest, kidnapping, and transfer to Israel by the Mossad. Between April 11 and December 15, 1961, in a converted theater in Jerusalem and with video footage that was transmitted throughout the world, the Eichmann Trial was held, a turning point in how Nazi crimes were perceived. Along with a multitude of journalists and international observers, Langbein was personally in attendance (still as a representative of the IAK, since the ultimate falling out occurred a short while later). This epoch-making trial marked, among other things, the beginning of the “era of the witness” (Wieviorka 1999). Moreover, the trip helped Langbein locate new witnesses and gather a number of contributions for the anthology he was preparing in those same months (Stengel 2012, p. 468).

The Frankfurt Trial, formally known as the “criminal case against Mulka and others,” began on December 20, 1963 and ended on August 19, 1965. A total of 360 witnesses were heard, including 211 former prisoners from 19 European countries, 91 former SS members, and 58 civilians. There were neither important war criminals nor bureaucrats sitting at the defendants’ table; instead, the people who had materially conducted the violence were tried: for the first time, the workings of the extermination machine were ascertained (Ponso, 161).

Langbein himself testified and was present in the courtroom almost every day of the trial (it lasted 183 days); he moved to Frankfurt and lived there for over a year. Besides personally overseeing the concrete details of the hospitality that was given to the former deportees who were called on to testify (many of whom were returning to Germany for the first time), offering them material and psychological support, he documented all the testimonies (sending his records to his wife in Vienna so she could transcribe them, Halbmayr 2012, pp. 93-96, Pelinka 1993, p. 102). Europäische Verlagsanstalt published this testimony in a two-volume edition about the trials (Langbein 1965).

In the meantime, one of the goals of East Germany was to legitimize itself on an international level as the only anti-Fascist German state (in opposition to the Hallstein Doctrine), in particular after the Berlin Wall was built in 1961. The Waldheim Trials, the first trials to be held in East Germany, had been conducted much earlier, between April 21 and June 29, 1950. 3,324 defendants were accused and tried for crimes against humanity; however, the trials caused a scandal in public opinion due to blatant procedural irregularities as to how the witnesses were heard and how the accused were defended.

However, a glaring attempt at legitimization was made in the following decade when Hans Globke was tried in absentia in 1963. In East Germany, Globke was a symbol of the scandalous continuity between the National Socialist regime and West Germany: as a lawyer and a councilor of the Reich Ministery of the Interior, he had helped draft the antisemitic racial laws; in the German Federal Republic of the 1950s, he became Secretary of State and one of Adenauer’s closest confidants. The trial resulted (in the absence of the accused) in a life sentence.

East Germany’s response to the Frankfurt Trial was prompt: in 1966, the Fischer Trial was held. In it, IG Farben, in the person of the doctor Horst Paul Fischer, was accused of being responsible for the death of 75,000 people; the defendant was condemned to death on July 8, 1966. In this case, too, it was a show trial that was ideally supposed to strike not only the individual defendant but the capitalist industrial apparatus that had colluded with National Socialism. This time, Langbein was not called on to testify, even though he had been the secretary of Eduard Wirths, Fischer’s superior at Auschwitz (Dirks 2006).

Austria

At the same time, Langbein had begun moving on the Austrian front as well, in an attempt to bring about an Auschwitz Trial there, too. It was not by chance that almost all of his attempts – he made his first accusation on March 31, 1960 against Georg Meyer, a doctor at Auschwitz – ended in failure: during the postwar period, no process of denazification had been activated in Austria, and there was a substantial continuity in the managerial class between the period when the country was occupied and after the war ended. The concept of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, a re-elaboration of the Nazi past, was countered by a national victimhood narrative, the so-called Opferthese, (Botz 1996, Weinke 2006, pp. 71-72). Starting in the 1970s, there were well-known cases in Bruno Kreisky’s social democratic government, with as many as four ex-Nazi ministers (and the relative controversy with Wiesenthal), and most conspicuously the election of Kurt Waldheim (a former Wehrmacht officer suspected of war crimes in the Balkans), first as Secretary-General of the United Nations (in 1971) and later as President of Austria from 1985 to 1992.

Between the 1960s and ‘70s, the Austrian judicial system opened investigations on more than sixty people, primarily under the pressure of Langbein and Wiesenthal. These people had been doctors, guards, technocrats, and members of the political and military administration at Auschwitz. In February 1962, Langbein and Wiesenthal pressed charges against Johann Schindler, the former adjutant to the commandant in Auschwitz, (Loitfellner 2006). Like in Frankfurt, the idea was to create a unitary trial, an Austrian Auschwitz-Stammverfahren, but the obstructionism of the judicial system on the one hand and the difficulties in tracking down witnesses on the other caused the project to founder after years of delay. Only in 1972, when Hugo Kresnik was named attorney general, were two trials finally held against four defendants (Walter Dejaco and Fritz Karl Ertl, from January 19 to March 10, 1972; and Otto Graf and Franz Wunsch, from April 25 to June 27, 1972); the defendants were found not guilty. Immediately afterward, the Minister of Justice Christian Broda ordered the cancellation of all the other trials. After having waited a decade, Langbein was no doubt disappointed at this disastrous outcome, but for him the true battle for justice for Nazi-fascist crimes was being conducted in the Federal Republic of Germany (Stengel 2012, pp. 546-7).

The 1970s

In Germany, the generational conflict sparked by the protests of 1968 was strongly influenced by the topic of coming to terms with the Nazi past. This was iconically exemplified when the young activist Beate Klarsfeld slapped Chancellor Kiesinger and accusatorially shouted “Nazi, Nazi!” at him during the CDU general assembly on November 7, 1968. But despite the number of investigations that were opened and the proceedings that were instituted, the trials were fundamentally a failure compared to the previous decade.

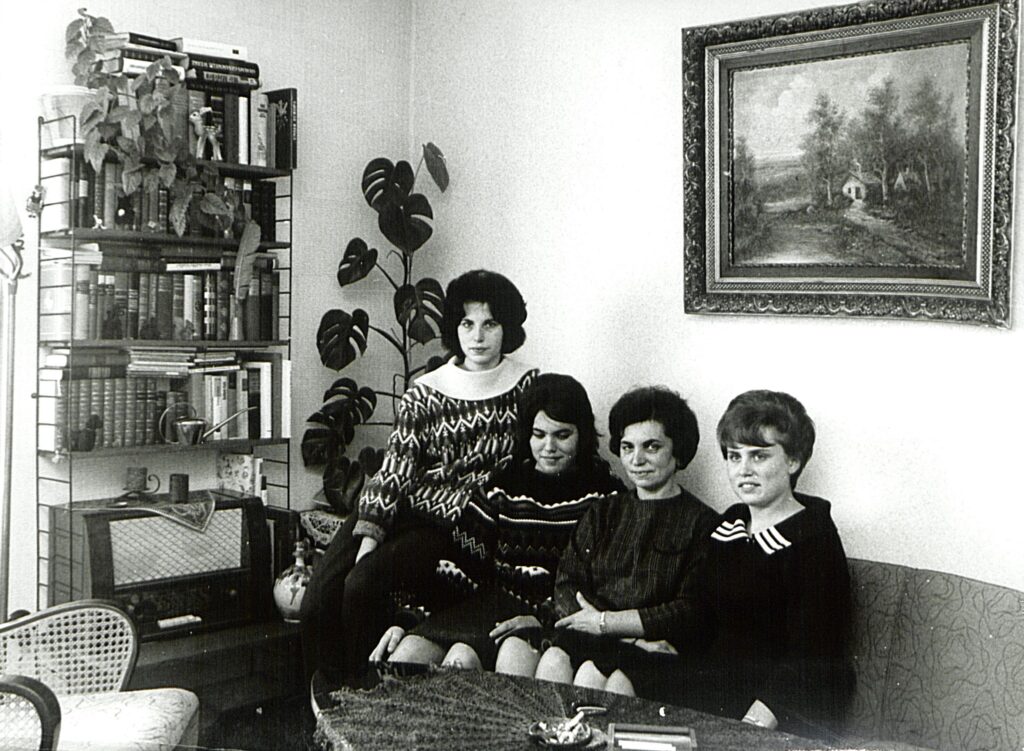

The Austrian trials, as we have seen, proved to be almost a joke: the correspondence between Langbein and Levi reveals that in April 1972, Langbein had not yet given up on finding witnesses for the Schindler case; Levi had given him the names of four Italians (Elena Napolitano, Giuliana Tedeschi, Luciana Momigliano, and Bianca Morpurgo, see letter 27), who nonetheless were unable to serve as witnesses.

Things were not going any better in the Federal Republic of Germany. On behalf of the CIC (Comité International des Camps), a new committee he had joined, in 1963 Langbein was already writing and disseminating a monthly informative bulletin among his network of acquaintances (No. 54, dated September 2, 1974, is attached to letter 047 of their correspondence), in which he also shared news about the trials and defendants. Langbein’s primary criticism of the ongoing trials concerned the delays and the ineffectiveness of the sentences. One particularly telling case concerned Albert Ganzenmüller, the Reich undersecretary who was in charge of the railways and thus implicated in the deportation of Jews. After fleeing to Argentina in 1945, he returned to Germany in 1955, where various trials were instituted against him; each time, they were suspended for lack of proof. The last trial, which was held in April 1973 by the court in Düsseldorf, was provisionally halted because of the defendant’s health problems and was terminated altogether in 1977.

Langbein also gives an account of various other trials that took place during the 1970s – in Mannheim (against Richard Pal), Hamburg (the Lublino Trial, the Slonim Trial, and the trial against Globocnik’s collaborators), Kiel (the Mogilëv trial), and once again in Frankfurt (against Gomerski) – pointing out their failures.

This context also includes the case of Friedrich Boßhammer, who was sentenced to life imprisonment in April 1972. In the 1960s the court in Dortmund had already begun investigating the former Sturmbannführer, one of Eichmann’s close collaborators, who was accused of having deported 3,500 Italian Jews. The CDEC (Center of Contemporary Jewish Documentation) became involved during the investigation, and Primo Levi and Leonardo De Benedetti were called on to testify (Levi 2015, p. 223 ff.). In 1972, Boßhammer was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment, but he died a few months after the verdict and never served time.

Thus, the main period of trials concluded in a minor key in the 1970s, and Langbein’s commitment to this specific battle gradually waned. Now, a new battle needed to be fought for memory, connected to the first but profoundly different: a battle against denialism and historical revisionism, and against the disturbing wave of neo-Nazi and neo-Fascist movements in Europe.