Hermann Langbein

Biography

by Alice Gardoncini, translation by Gail McDowell

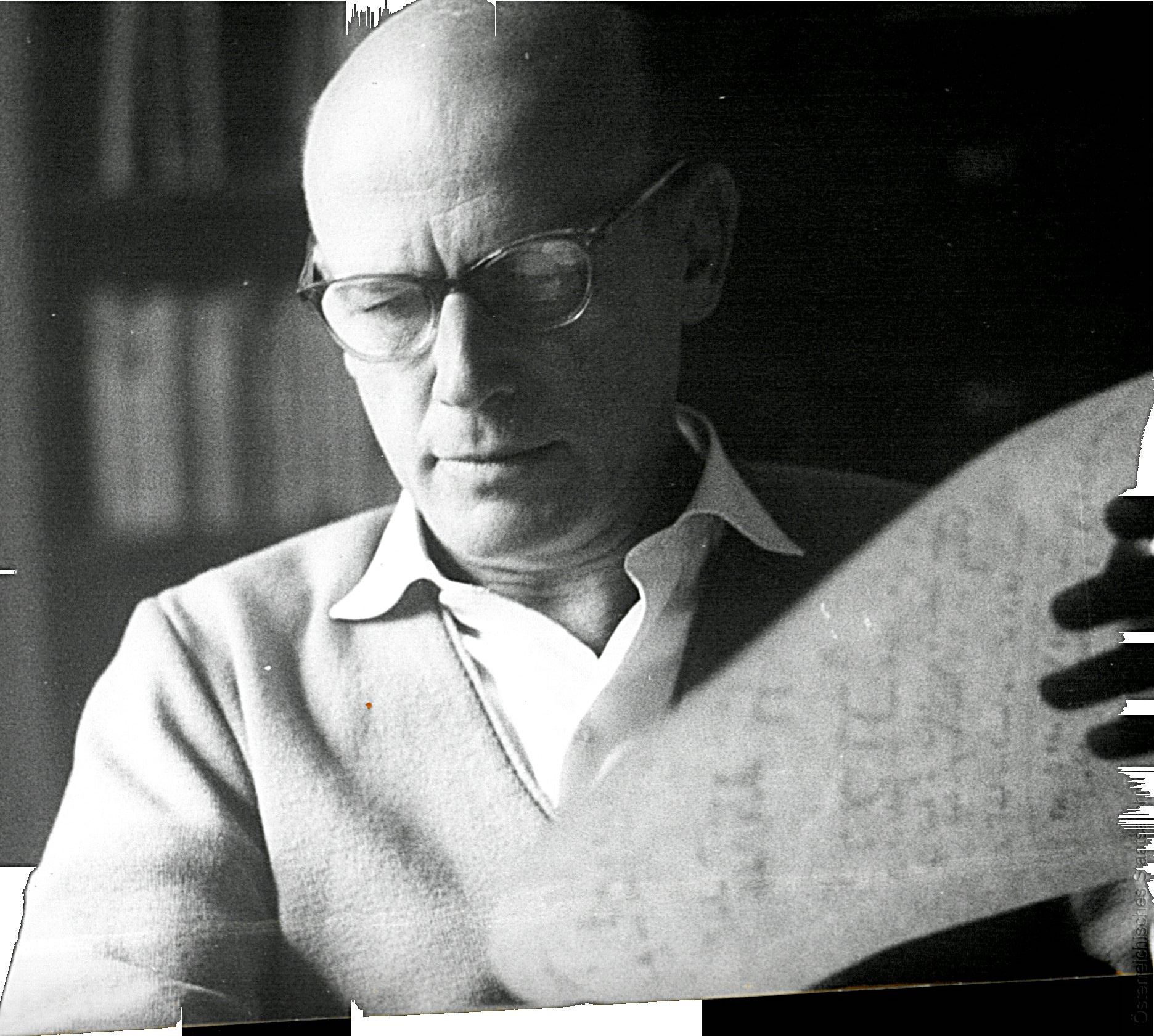

A formidable man

“The author, H. Langbein, is a formidable man, a former communist, a former legionnaire in Spain, later imprisoned in a P.O.W. camp in France, deported to Dachau and then to Auschwitz, a very active member of the Resistance inside the Lager, and the ‘right-hand man’ of an SS doctor.” This is how Primo Levi presented Hermann Langbein to the publishing company Mursia on 6 October 1973, when he proposed an Italian translation of Langbein’s monumental Menschen in Auschwitz, now a classic of concentration camp historiography (Langbein 1972).

It was probably not by chance that Levi chose the adjective “formidable” to define Langbein. Formidable – from the Latin formidare, i.e., to fear – means fearsome, and in fact, throughout his lifetime, Langbein was one of the most redoubtable, consistent, and tenacious adversaries of every form of fascism. He started by conducting clandestine political activity in Vienna during the 1930s, became involved in the Spanish civil war, was a member of the resistance in the Lager, and lastly, during the post-war period, he painstakingly hunted down Nazi criminals, laid the groundwork for their trials, and gathered testimony.

His early years in Vienna: communist or actor?

Hermann Langbein was born in Vienna on 18 May 1912 into a lower-middle-class family: his father, a Jew who had converted to the Evangelical faith, worked as an accountant in a textile factory; his mother was a teacher. His brother Otto, who was one and a half years older, played a decisive role in Hermann’s upbringing and future political choices. When their mother died of cancer (Hermann was only twelve years old), her sister, “Tante Else,” helped the family. She and the two young brothers shared a political vision that became increasingly distant from that of the boys’ father, who supported a type of nationalism that drew its inspiration from Bismarck. Very soon, starting in the early 1930s, the two brothers drew closer to the positions of the Communist Party, which they joined: Otto did so in 1932 and Hermann in early 1933, just a few months before the party was outlawed.

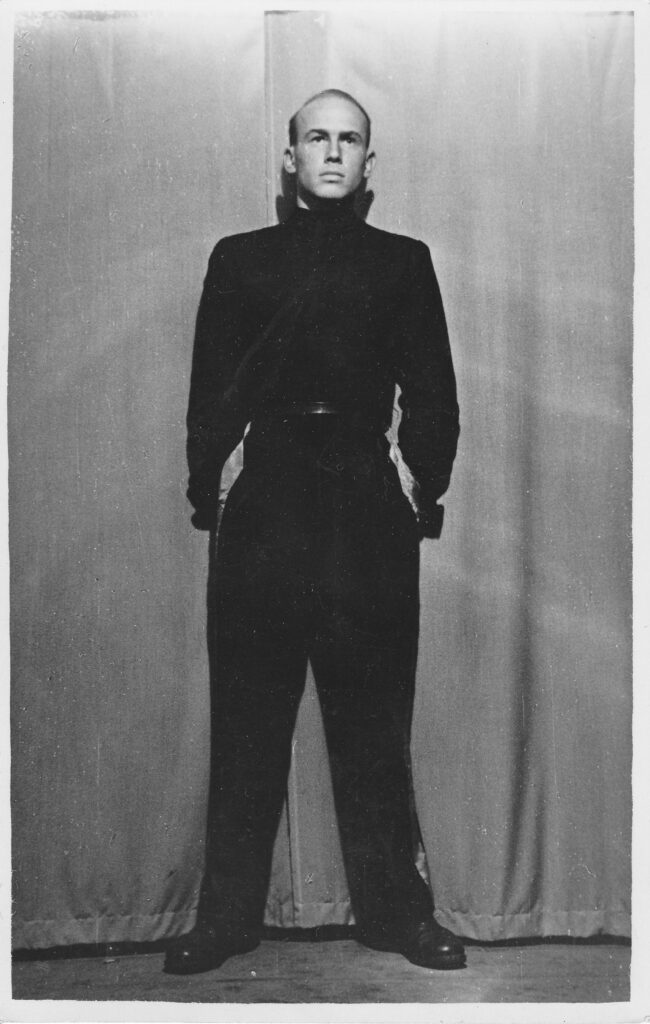

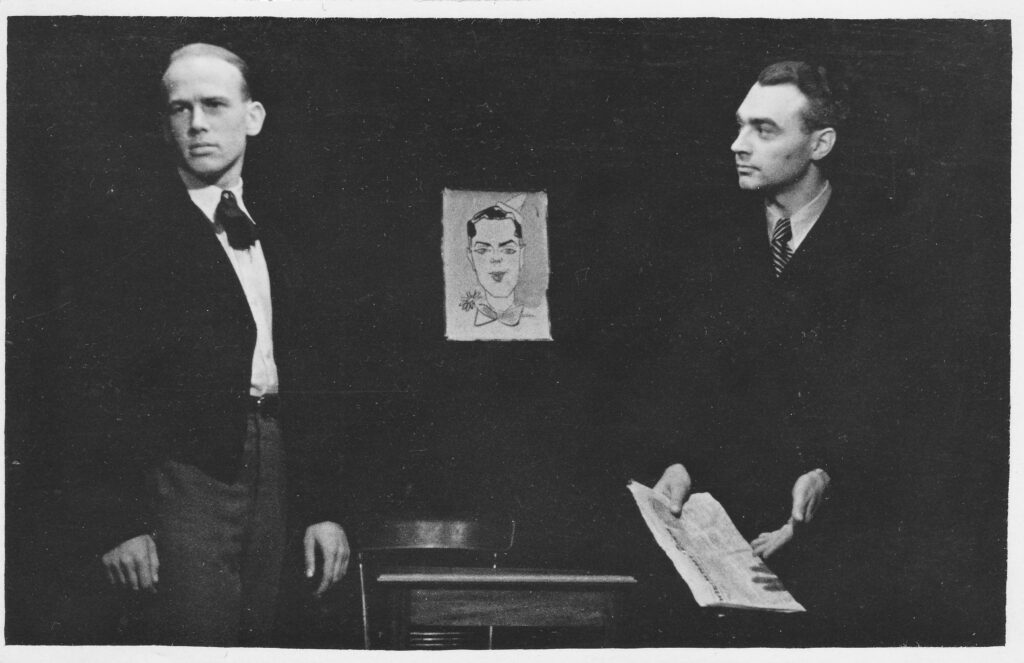

Besides his passion for politics, Hermann soon revealed a passion for the arts. Shortly after receiving his high school diploma, he decided to pursue an acting career, once again against the wishes of his father, who wanted him to become a doctor. In the fall of 1931, he became an apprentice actor at the Volkstheater in Vienna, using the stage name Hermann Lang, and began to frequent various cabaret groups (including the Stachelbeere). It was a period of great enthusiasm and lightheartedness, and ample documentation of it still exists today because, right from an early age, Langbein was a cataloger: he loved to take note of what he was doing and reading with surprising precision and detail. As a result, his legacy numbers thousands of documents, including notebooks in which he listed and commented on the books he read, as well as detailed lists of all his stage appearances (Halbmayr 2012, 21-25).

Faced with the difficult choice between becoming a communist or becoming an actor, the young man initially tried to reconcile the two paths (Stengel 2012, 31). After his father died in 1934, he went to live with his brother in a shared apartment that became the headquarters of a series of clandestine activities, including the production of the cyclostyled newspaper “Klassenkampf” [Class Struggle]. But the apartment soon ended up on the police radar. Hermann was repeatedly arrested (the first, preemptive arrest took place in February 1935, and others followed over the course of the next two years), and he was obliged to abandon his theatrical career.

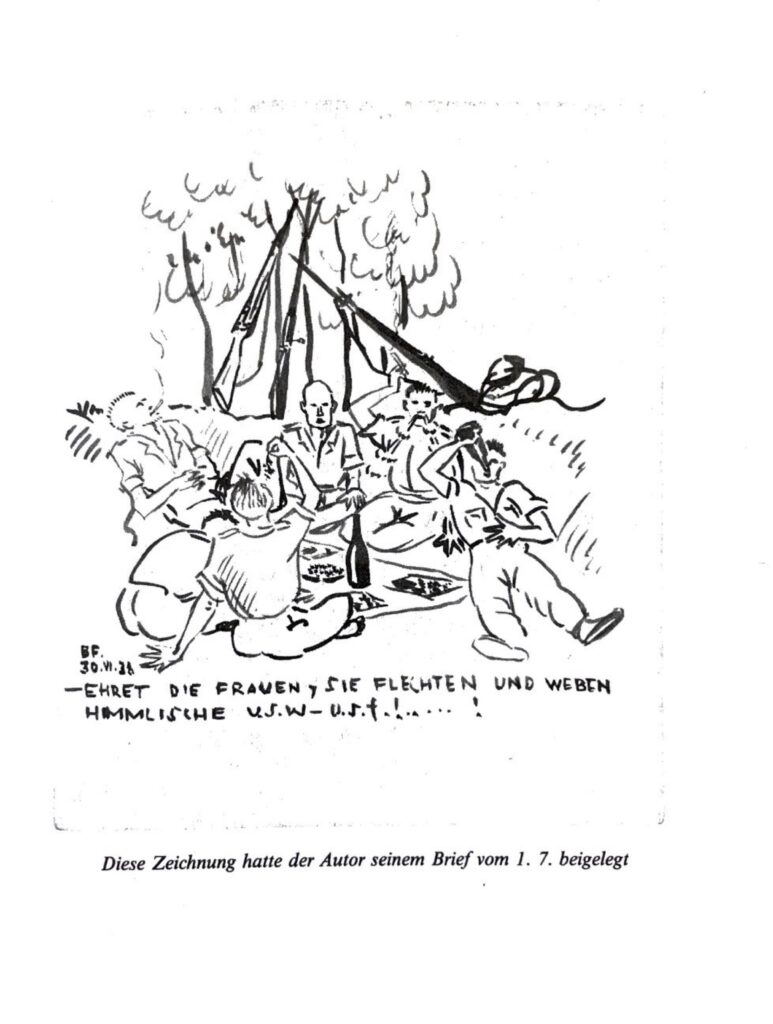

Pasaremos. The International Brigades and the French concentration camps

Following the Anschluss of Austria in 1938, Langbein, who at that point was known to the authorities as a political dissident, was forced to leave Vienna. On March 22, 1938, he left with his partner, Margarete (Gretl) Wetzelsberger, who was also a Communist; the pair crossed the border illegally, fleeing first to Switzerland and then to Paris, where Hermann’s brother Otto had preceded them. Gretl remained in Paris with Otto, who had contracted a lung disease, and Hermann left for Spain on April 9. With a group of other Austrians, including his cousin Leopold Spira, he joined the International Brigades in Figueres, Catalonia. He described the eight months they spent with the volunteer combatants as a running commentary in long letters he sent to Gretl and Otto, and which were later collected in a volume (Langbein 1982). The most intense moment was in June 1938, when he took part in the battle of the Ebro. Over the course of those months, he also edited the newsletter of the XI brigade, to which he belonged (Halbmayr 2012, 44).

In February 1939, after the Republicans were defeated and the International Brigades were demobilized, the veteran volunteers were interned in various French prison camps. Langbein, along with almost all the other Austrians, was sent first to Saint-Cyprien, one of the notorious Camps de la plage (February-April 1939), then to Gurs (April 1939-April 1940), and lastly to Le Vernet (April 1940-April 1941). This was his first, harsh experience of imprisonment. Despite hunger, cold temperatures, and the violence to which they were subjected, Langbein and his companions organized a popular university at Gurs (the “Österreichische Volkshochschule Gurs”), which he himself directed and where he taught German. The prisoners were allowed to receive visitors, and in October 1940 Langbein’s brother Otto visited him at LeVernet; the two were reunited only after the war was over.

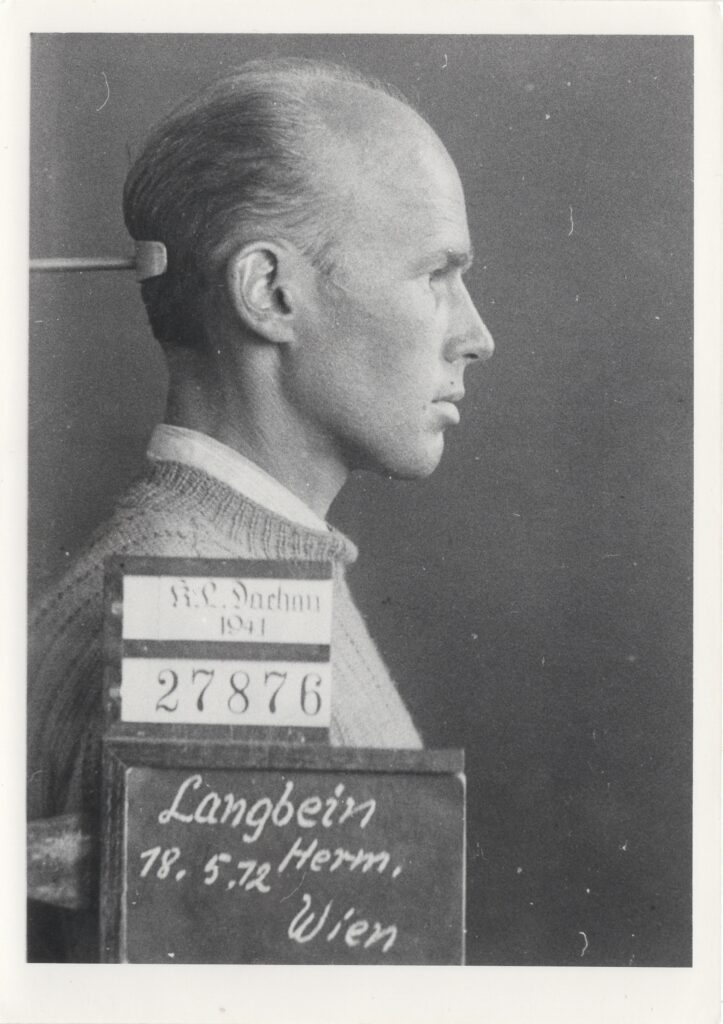

Dachau, Auschwitz, Neuengamme

After France was occupied, the prisoners passed under the jurisdiction of the Gestapo. Along with 145 other Austrians, Langbein was sent from Le Vernet to Dachau, where he was held as a political prisoner, a Rotspanier, i.e., a “red” fighter in the Spanish Civil War. Since he knew how to write in shorthand, use a typewriter, and had studied Latin, he became the personal secretary of Dr. Rudolf Brachtel and also came into contact with another doctor, Edward Wirths.

On August 19, 1942, Langbein and sixteen other prisoners were sent from Dachau to Auschwitz, where a typhus epidemic had broken out. He was erroneously listed as a nurse, but his name may have ended up on the list due to the rivalry between social democratic and communist prisoners at Dachau (Halbmayr 2012, 70). When Edward Wirths also arrived at Auschwitz, he recognized Langbein and chose him as his secretary. The privileged position Langbein thus acquired let him observe and comprehend the camp’s dynamics in detail. He had access to confidential information, including statistics regarding the prisoners who were killed, and he was an eyewitness to the transportation of corpses by the Sonderkommando and the killings in the gas chambers. The office where he worked was located right in front of the Altes Krematorium, the crematory (Langbein 1949, 114). He and other prisoners of various nationalities organized the Kampfgruppe Auschwitz (Langbein 1962, 227-38), a resistance movement (to which the Poles Józef Cyrankiewicz and Tadeusz Hołuj also belonged); his job was to gain the trust of Wirths and influence him in order to obtain better conditions for the prisoners.

Langbein remained at Auschwitz until August 1944, when he was moved to the Neuengamme concentration camp, south-east of Hamburg. He managed to avoid the death marches and on April 11, 1945, while prisoners were being transported, he escaped. He returned to Vienna on May 18, 1945, after having spent almost six and a half years in concentration camps.

The post-war period in Vienna (1945-1958)

Like Germany, Austria was divided into occupation zones by the four victorious powers, including the Soviet Union. Langbein returned to Vienna full of expectations, and his first years there were marked by euphoria and his membership in the Austrian Communist Party (KPÖ): he became a functionary, a member of the KPÖ Central Committee, and the director of the party’s schools. But already by the end of the 1940s, the situation had deteriorated; Langbein was embittered by what he perceived as a lack of interest in the accounts of people’s experiences in the Lagers (Pelinka 1993, 37). In 1949, he published Die Stärkeren. Ein Bericht (Langbein 1949). Four years earlier, in Hanover, on April 22-23, 1945, he had dashed off an almost 30-page report about Auschwitz as testimony for the British authorities (Langbein 1945). Because of its length and the purpose it served, his report is comparable to the one Leonardo De Benedetti and Primo Levi wrote in Katowice for the Soviet government, today known as the Rapporto medico-sanitario(OC I, 1177-94).

In 1951, after criticizing Friedl Fürnberg, the future secretary general of the KPÖ, Langbein was expelled from the Central Committee. In 1953, the party asked him to create and run a German-language radio station in Budapest; he moved there with his wife (Aloisia Turko), a journalist and fellow communist. They had married in 1950; their first child, Lisa, was born in 1952. When the family moved to Budapest, Turko was expecting their second child, Kurt. Langbein considered this assignment a form of punishment, and he became increasingly critical of the Soviet Union during the year he spent in Hungary. After returning to Vienna, he worked as an editor at the Österreichische Zeitung (1954), the communist party newspaper, and then as editor-in-chief of the Neuen Mahnruf (1956).

In May 1954, the Féderation Internationale des Résistants (FIR) founded the International Auschwitz Committee (IAK) in Vienna; Langbein was appointed secretary general. This brought him into contact with many Auschwitz survivors of various nationalities, as witnessed by the profusion of documents in his archive. Among the Italian survivors, a fundamental role was played by Leonardo De Benedetti, whom he met in 1955. Through him, Langbein received a list of other Italians to contact, including Primo Levi (cf. De Benedetti).

Over the following years, his disagreements with the Austrian Communist Party grew. Unlike his wife and his brother, Langbein remained a party member even after the events in Hungary, but he was expelled in 1958, when, in the name of the International Auschwitz Committee, he protested against the executions of Imre Nagy, Paul Maleter, and three other victims of Soviet justice (Halbmayr 2012, 144).

From the IAK to the CIC (1958-1961)

The growing tension in Europe sparked by the Cold War coincided with an exacerbation of the relations between Langbein and the IAK: in 1958, he was demoted from secretary general and put in charge of the trials and the compensation paid to survivors and family members of victims. Even though the Committee declared itself in favor of a non-party statute, in July 1959 the Polish members, headed by Tadeusz Hołuj, decided to create a second headquarters in Warsaw, effectively marking a pro-Soviet turn.

This was the start of a complicated phase for Langbein. While he, H.G. Adler, and Simon Wiesenthal were searching for financing to found a new (neutral) committee, in October 1960, on its own initiative, the IAK signed a contract with Europäische Verlagsanstalt (EVA) for an anthology of accounts and memoirs about Auschwitz. It was the first editorial project of its kind in Germany and in the German language, and its release was meant to coincide with the big Auschwitz trial that was being prepared in Frankfurt. The editors were to be Hermann Langbein, H.G. Adler, and Ella Lingens-Reiner, the president of the Austrian Concentration Camp Community (Österreichische Lagergemeinschaft Auschwitz, ÖLGA).

From December 1960 relations with the IAK deteriorated even further, and even though Langbein spent almost all of May 1961 in Jerusalem as a Committee envoy to follow the Eichmann trial, he was ultimately exonerated from every role within the IAK, as of July 1961.

At the same time, the anthology project was at risk: the Warsaw wing (Through Stefan Haupe, the delegate for administration and finance) contacted the publishing house to exonerate the editors; in reply, the publishing house canceled its contract with the IAK and signed a new one directly with the editors. At that point, the Committee put pressure on the Eastern-block authors to have them withdraw their contributions, and tried to discredit the editors by claiming that they wanted to profit from the initiative (Stengel 2012, 280-342). But in spite of everything, the anthology, entitled Auschwitz. Zeugnisse und Berichte, was finally published in 1962. It contained two chapters from Se questo è un uomo (If This Is a Man) by Primo Levi (“L’ultimo” [“The Last One”] and “Storia di dieci giorni” [“The Story of Ten Days”]). Levi’s book, translated into German by Heinz Riedt, had been published in November 1961 in West Germany. To avoid polemics, the authors of the anthology agreed to waive payment, and all the proceeds were destined to former deportees in difficulty.

At this point, it was crucial for Langbein to have a position on an international committee, both for economic reasons and in order to attend the trials in an official capacity. In 1961, he became the secretary of the ÖLGA, even though it was not an international committee and, above all, did not have the economic means to guarantee him a salary. Finally, on January 20, 1963, the International Committee of the Camps (CIC) was founded, and he was appointed secretary. The association’s address (as was the case for the IAK) was his home address in Vienna; the financing was paid by the UIRD (the de facto pro-West counterpart of the FIR, Halbmayr 2012, 312).

Through the 1960s, Langbein collaborated actively in Nazi hunts conducted by Simon Wiesenthal, Thomas Harlan, and Fritz Bauer, which led to the arrest of Nazi criminals still on the loose (cf. Raja), and he published a series of works (Langbein 1963, 1964, 1965) documenting the Frankfurt trials (1963-65). In the early 1970s, Langbein was also involved in preparing and attending the Austrian Auschwitz trials which, after ten years, were finally held in Vienna in 1972 but concluded with a disappointing verdict that acquitted the four defendants, Dejaco and Ertl (in March), and Graf and Wunsch (in June) (Loitfellner 2006, cf. Nazi trials).

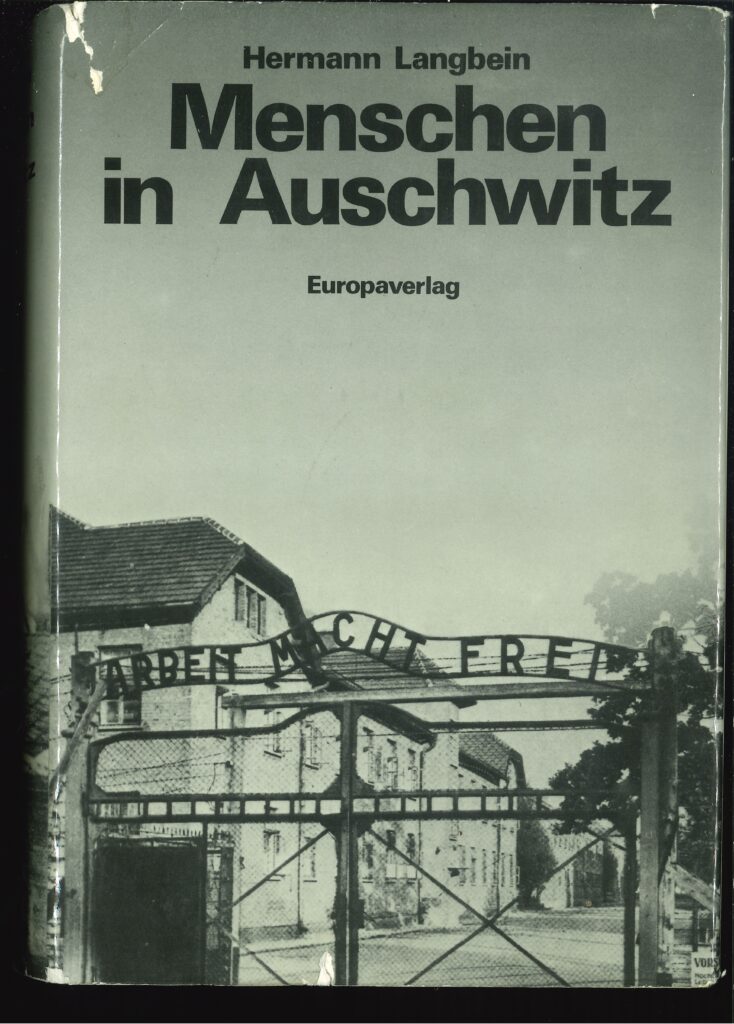

Menschen in Auschwitz

In the early 1960s, Langbein found himself in difficulty after being expelled from the Communist Party. He was helped by acquaintances and friends from various countries: Christian Broda, at the time Austria’s Minister of Justice (and a member of the SPÖ), put him in contact with Europa Verlag, with which Langbein published various works, from trial reports (the first in 1963) to Menschen in Auschwitz (in 1972). Hety Schmitt-Maas, head of the Ministry of Culture’s press office in Hesse during the 1960s, activated a series of contacts and created an epistolary network focusing on the Langbein’s question. She was eventually able to procure him a fellowship (which lasted three years, until 1968) of the New Land Foundation, run by Joseph Buttinger and Muriel Gardiner (Halbmayr 2012, 247-49). Thanks to this financing, Langbein was able to dedicate himself to writing his important book about Auschwitz.

Twenty years had passed since his Lager experience, but paradoxically it was his work at the trials, during which he inevitably came into close contact with the defendants, that allowed him to put the criminals into perspective, to the point of considering them simply human beings and not demons, thereby acquiring the emotional detachment he needed in order to write. As he recounted later in an interview: “By the end of the trial, to me Klehr [Josef Klehr] had become nothing more than an elderly criminal who was defending himself ineptly and was no longer the person he had been in Auschwitz. When I realized this, I said to myself: now I can write.” (Pelinka 1993, 104) Thus, the human beings [Menschen] in the book’s title were no longer the prisoners but all the humanity involved in the annihilation machine, hence the SS, too.

The 1980s and the initiative “Contemporary Witnesses” [Zeitzeugen]

After the years he devoted to Menschen in Auschwitz, Langbein began occupying himself once again with the resistance in concentration camps (Langbein 1980). Then, in reaction to the wave of denialism sweeping through Europe during the 1980s, he launched his last great project: a substantial documentation about the gas chambers, which led to a research committee and a publication, Nationalsozialistische Massentötungen durch Giftgas. Eine Dokumentation(Langbein 1986).

During the final part of his life, Langbein devoted himself primarily to the young generations. His first experiences speaking in schools as an Auschwitz witness date back to the years of the Frankfurt trials (1963-65), in Germany(Langbein 1967). But toward the end of the 1970s this initiative took on a more institutional and permanent form. Langbein created an official program for Austrian schools (Zeitzeugen in der Schule) that was approved and active throughout the 1980s, and, with the support of the Austrian Ministry of Education, also included video registrations of his encounters with students (Halbmayr 2012, 207-26). In May 1986, in his last letter (link) to Primo Levi, he wrote: “But I still go to schools […]: I feel very comfortable in discussions (if they are conducted intelligently, as is usually the case). I do not get tired of it, either. And especially now, when so many terrible things have been revived during our federal presidential election, I feel our obligations in this regard stronger than ever.” His final conference in a school was held in Vienna on March 31, 1995, seven months before he died.

References and bibliography

Levi’s letter to the publishing company Mursia, dated October 6, 1973, is conserved in the Primo Levi archival holdings, Fondo Primo Levi, Corrispondenza, Corrispondenza generale, Fasc. 7, sottofasc. 10, docs. from 30 to 32, ff. 335R and v.

Langbein’s letter to Levi dated May 10, 1986 is conserved in the Primo Levi archival holdings, Fondo Primo Levi, Corrispondenza, Corrispondenza generale, Fascia 1s7, sottofasc. 8, docs. from 12 to 14, ff. 246r and 246v. The reference is to the Waldheim case: that year, the Austrian presidential election was won by Kurt Waldheim (1918-2007), who was known for his past in the SA (Sturmabteilung, a paramilitary wing of the German Nazi Party) and for war crimes committed in the Balkans when he was a Wehrmacht officer. Levi also commented on the Waldheim case in an interview with Daniela Dawan in July 1986 in the “Bollettino della Comunità Israelitica di Milano,” now in OC, III, pp. 607-10, at p. 608.

The report on the camp’s hygienic-sanitary organization, written by Leonardo De Benedetti and Primo Levi, can be found in the first volume of the complete works of Levi, OC I, pp. 1177-94, transl. Judith Woolf, Auschwitz Report – titolo originale Report on the Sanitary and Medical Organization of the Monowitz Concentration Camp for Jews (Auschwitz - Upper Silesia), London: Verso, 2006.